Replay: In the last three decades of the 20th century, when film was still the dominant medium, there was one piece of equipment that, close to being universal, was an essential piece of kit for the smallest documentary to the grandest feature film. It was the Swiss-made Nagra audio recorder. And perhaps the most definitive of these was the Nagra IV series.

Stefan Kudelski, a young Polish émigré living in Switzerland, developed the first Nagra in 1951 (apparently when asked what the hell it was, Mr Kudelski replied ‘Nagra’ – Polish for ‘it records!’). Nagra I was the prototype and Nagra II was rarely seen and both of these were actually clockwork-driven. The Nagra III of 1961, however, was a huge success. A small, portable, very high quality recorder with one mic input and Kudelski’s Neo-Pilottone system, it revolutionised location filmmaking.

In those days, film cameras needed to be synced to the audio recorder. Initially, this was done with a sync cable, putting a pulse from the camera onto the tape via a cable. Soon this was replaced by crystal sync – quartz crystal would control the camera at precisely 24 or 25 fps. A similar crystal would put a sync pulse on the tape (tape can stretch and slip, so just controlling the capstan speed on a tape recorder would not do the trick). The Neo-Pilottone system, rather than recording the sync pulse on a single separate track, used two tracks out-of-phase with each other which would cancel each other out when played over a regular playback head, thus avoiding crosstalk.

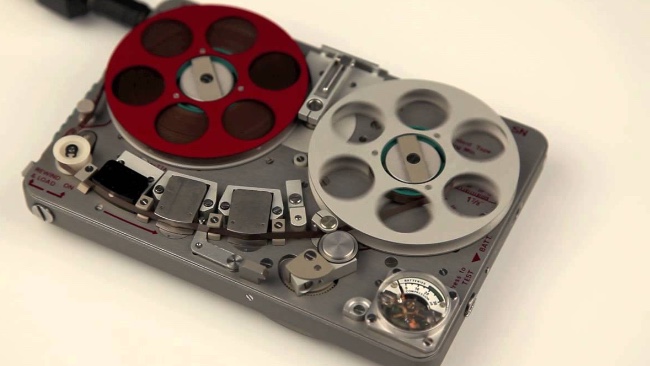

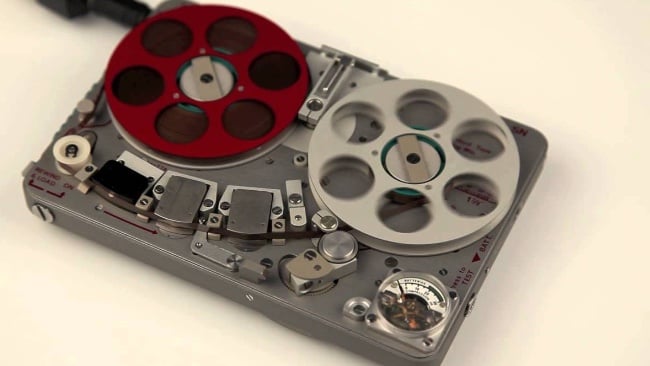

The Nagra 4.2

But it was the Nagra IV series – in particular, the Nagra 4.2, introduced in 1970 – that became the workhorse of the industry. Running 5” spools of ¼” tape and powered by 10 standard ‘D’ cells, the Nagra 4.2 was a mono machine with two powered mic inputs, and very high quality pre-amps, equalisers and limiters. It was extremely reliable, robust and finely engineered in every way. It looked like a piece of precision scientific equipment – which it sort of was. The Nagra had a beauty that came out of purely functional, high quality engineering. Every knob and lever on the Nagra appeared to be custom-machined – no obvious generic parts and no compromise in design. That sort of quality came at a price – in today’s money, a Nagra 4.2 would cost the equivalent of around $10k. Subsequent versions would offer stereo (IV-S) and timecode (IV-STC).

The Nagra could also be synced in playback mode – the recorded pulse on the tape could either be synced to an external mains frequency or to the Nagra’s own internal crystal. This was the standard form of sync playback used for shoots during the rock promo boom of the late 80s and early 90s.

Alternative versions

There were other great and eccentric analogue Nagras – the miniature Nagra SN, which used 1/8th inch tape, became the definitive spy recorder (allegedly it was commissioned by President Kennedy for the US Secret Service). The Nagra IS (standing for ‘idiot proof’ in Polish) was a smaller, simpler recorder that had all the instructions printed on the machine itself. The Nagra E was an even humbler machine with no sync options, designed for radio reporters. The Nagra T was a huge, beautiful machine that would be found in post production suites for automatically syncing up to time-coded film rushes with great speed and elegance. There was even a rarely seen 1” video recorder, made in co-operation with Ampex, which came out just as Betacam was becoming the broadcast video standard.

Sadly, Nagra lost their way when we moved to digital. While digital technology offered cheap, lightweight, decent quality machines, Nagra stuck to their tradition of making big, very high quality and very expensive machines. The Nagra D, introduced in 1992, was a reel-to-reel digital machine capable of 96kHz/24bit recordings, but it was far too big and expensive for location work.

The introduction of DAT

DAT was becoming common in the industry in the early 1990s and, although it had its issues, DAT machines were portable and cheap. Nagra introduced the hard drive based digital Nagra V around the turn of the century, which mimicked the look of the classic analogue Nagra with a familiar lever transport switch and a Perspex lid – for no good reason since there were no reels under the lid or transport mechanism to switch on. I only remember one shoot where a Nagra V was used and, sadly, it broke down (the first and only time I recall a Nagra failing).

Nagra is no longer a force to be reckoned with in the film and TV industry, but the brand carries on. They offer a range of small audio recorders for radio journalists, made in the Far East. And finally there is a rarely seen, Swiss-made Nagra Seven, a 2-channel machine recording onto SD cards, that can be yours for around $4k.

Nagra also offers a range of extremely high-end audiophile gear for the domestic market, that retains the classic Nagra look. And when I say “high-end”, a pair of Nagra HD monoblock amps, an HD pre-amp and an HD DAC will set you back £170,000 (yes, that is four zeros - I haven’t included speakers as Nagra don’t make them). I am sure they are truly wonderful pieces of kit, but there is something sad about Nagra today. The Nagra was a functional machine, totally unpretentious and, considering the quality of its engineering, good value for money. I don’t think you can say the same of the current hi-fi range.

The Nagra V

On the positive side, there are many beautiful Nagra analogue machines running today – you can pick up a 4.2 on eBay for under £1000. There are analogue enthusiasts who believe there are no finer ways of recording an orchestra than plugging a pair of high quality mics straight into a stereo Nagra. And who am I to argue with that.

Tags: Audio

Comments